Uncovering an Event That Devastated New York City

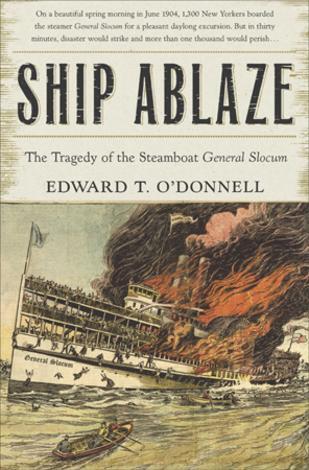

Ship Ablaze

The Tragedy of the Steamboat General Slocum

Edward T. O'Donnell, Professor, Holy Cross College

Ship Ablaze tells the extraordinary story of the burning of the steamboat General Slocum, the deadliest day in New York City history before September 11. More than 1,000 New Yorkers perished on June 15, 1904, when their steamboat burst into flames on the East River. A panicked and untrained crew, coupled with rotten life preservers and inaccessible lifeboats, turned a small storage room fire into a human tragedy of immense proportions. News of the horror made headlines around the world and elicited an enormous outpouring of sympathy and donations. Later, as evidence of negligence and corruption on the part of the steamer's owners mounted, sympathy turned to outrage and demands for justice that were never fully met. Ship Ablaze brings to life this gripping tragedy and the wider, compelling story of innocents lost, heroes made, and a city and people that overcame.

Testimonials

To those standing on shore or on the decks of nearby rescue vessels, the sight of the Slocum as it steamed at full throttle upriver almost defied description. "No artist," wrote a journalist in the aftermath, "unless he dipped his brush in the colors of hell, could portray the awful scene of a majestic vessel, wrapped in great sheets of devouring flames…"

Superintendent Grafeling of the gas works at Casino Beach near Astoria noticed smoke coming from near the port bow of the steamboat. He grabbed his field glasses and trained them on the strange spectacle. Immediately he saw bright orange shards of flame shooting out from the clouds of smoke. He knew then the boat was on fire, but wondered why the band continued to play.

William Halloway, an engineer on a dredge at work just off the Astoria shore saw the burning vessel and let fly four loud blasts from his steam whistle as a signal to other boats that the Slocum was in trouble. He then set off in hot pursuit. He was followed by Captain McGovern of the launch Mosquito who was employed on the same project and countless others, including eleven members of the Bronx Yacht Club, put out in three small launches.

On the Bronx side, Officer John A. Scheuing of the 34th Precinct was walking his beat along 138th Street near the water when he heard someone shouting about a steamer on fire. Looking down a side street that led to the river, he saw the Slocum coming upriver covered in flames. He bolted across the street to where a soda wagon stood and ordered the driver to take him to the river's edge. With a crack of his whip, they were off, scattering pedestrians and other vehicles that lay in their path. At the water’s edge and Scheuing jumped from the wagon and ran for the pier. Up ahead, he could see several small boats and beyond them the burning wreck of the Slocum as it approached North Brother Island. He jumped in a small rowboat and rowed as fast as he could to the scene of the disaster.

Scheuing was followed almost immediately by several other policemen who likewise put out in boats. Officer James A. Collins was at the East River near 134th Street when saw "a solid mass of flames" moving upriver. He ran to a nearby call box and got word to the fire department. Then he sprinted two blocks to a dock at 136th Street and with another policeman, Officer Hubert C. Farrell, commandeered a nineteen-foot boat and instructed its mate to make for North Brother Island.

Moments after they cast off, Engine Company No. 60 and Ladder No. 17 roared to the river's edge expecting to find the Slocum at one of the nearby piers. In frustration they watched the burning boat moving away from them and knew there was nothing they could do. Nearby, however, one piece of firefighting apparatus was heading off in pursuit, the fireboat Zophar Mills.

Out on Rikers Island where the city maintained a prison workhouse, two inmates saw the Slocum pass and ran for a boat. John Merther and Dan Casey knew they were taking a big risk, for their actions might easily be taken for an escape attempt, but there was no time to seek permission. Fortunately, when they reached the small skiff, they were met by one of the workhouse doctors who joined them.

Some who saw the Slocum that morning were in a better position than others to offer assistance. One of them was John L. "Jack" Wade, a tough harbor rat of a tugboat captain. Somewhat slight of build, he nonetheless exuded strength and self-assuredness. His tug, named John Wade in honor of his father, was a workhorse of a boat that was not much to look at, but capable of performing all manner of jobs on the New York waterways. While many of his fellow captains piloted a tug for one of the big towing companies like Moran or for one of the railroads, Wade was an independent operator. He owned the John Wade outright and earned his living working job to job along the busy waterfront, "in the manner of a cruising cabman on land," according to one description.

He was working on North Brother Island when he spied the Slocum charging upriver, a mass of smoke and flame. Some captains in his position that morning hesitated and some looked the other way, certain that others would come to the steamer's aid. They had in mind men like Jack Wade, tug captains who acted on instinct when sighting a boat in distress. It did not matter if he knew the vessel or the captain -- though in this case he certainly knew both -- for among men of his breed there was a code of honor that demanded only one response: to offer immediate assistance. This was not a job, but an obligation.

It took Jack Wade only a second or two to act. From a distance, the steamer (the Slocum by all appearances) looked to be in bad shape and getting worse by the second. But Wade had seen a lot of ship fires in his day, including that day four years earlier when the four German Lloyd liners caught fire in Hoboken. Wade and his men had been in the thick of it that day on the Hudson and witnessed truly horrifying scenes of death and destruction—scenes not soon forgotten, even by a hardened tug captain. This situation looked bad, but obviously a far cry from the day when nearly four hundred perished on these waters. Or so it seemed.

(c) copyright Broadway Books, 2003